FEBRUARY 1, 2024 | Rayliant

While a rapid rise in Treasury yields through mid-October threatened to derail investors’ holiday cheer, the Fed swept in like Santa Claus, delivering an early present to investors: dovish December dot plots suggesting rate cuts were in store for 2024. Yields quickly retreated as traders moved to price in twice as much easing as the Fed had tipped, leading to a solid quarter for stocks and bonds, alike. Below, we highlight themes and data the team at Rayliant is following going into the new year, opining on the prospect of rate cuts and how much of that good news might already be baked into prices.

Rayliant Global Advisors is a global investment manager with offices in Los Angeles, London, Hong Kong, Hangzhou and Taipei. With over US$15-billion in assets linked to Rayliant's strategies, its clients include some of the world's largest sovereign wealth funds, pension plans, and other institutional investors. Rayliant's award-winning team is an independent advisor to East West Bank regarding global economies and markets. East West Bancorp, Inc. (the parent company of East West Bank) holds a 49.9% stake in Rayliant Global Advisors.

Quarterly Commentary: Asset Classes

Equities

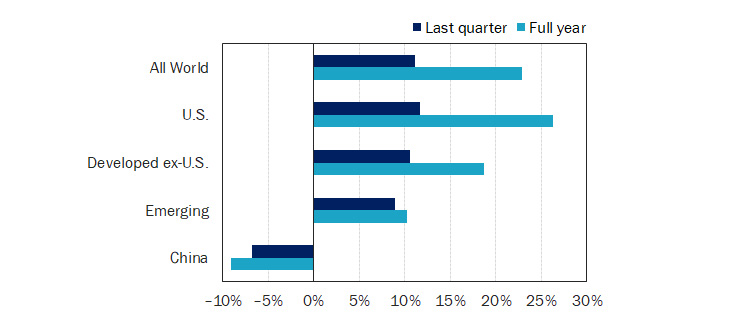

After showing weakness in the third quarter as yields surged and investors began questioning the soft- landing narrative, macro data throughout Q4 renewed markets’ confidence in the strength of the US economy, culminating in a December FOMC at which the central bank revealed it was contemplating rate cuts in 2024. That last development, in particular, sent equities and other risk assets into rally mode going into the year end (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Equity Market Performance (Returns as of 31 December 2023)

(Source: MSCI ACWI, S&P 500, MSCI World ex-USA, MSCI Emerging Markets, and CSI 300, all expressed in USD, except CSI 300 in CNY, via Bloomberg.)

US stocks led the way, with the S&P 500 climbing 26.3% in Q4 as investors digested cooling inflation and that dovish pivot in the Fed’s messaging. Developed markets outside the US likewise posted impressive numbers, returning 22.8% for the quarter. Stocks in the UK and Eurozone, where economic conditions are a bit weaker than in the States, nevertheless rallied, rising by 7.9% and 15.8%, respectively, as inflation in those regions also cooled and markets moved to price more aggressive cuts. Concern over China’s economic growth and issues in its property sector dragged emerging markets lower, though EM stocks still managed to post a 10.3% gain in Q4.

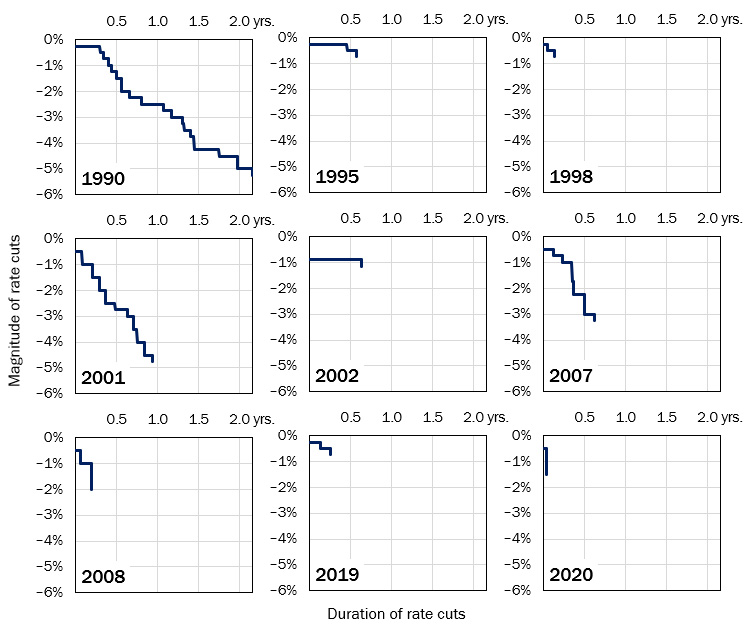

For much of the last two years, all eyes have been on the Fed for clues as to where rates are headed, as the central bank balanced risk of complacency in its fight against inflation, on the one hand—easing too soon and letting prices reaccelerate—versus overshooting and leading the US into a hard landing. As the Fed’s December meeting has got investors thinking about what it might look like if rates come down in 2024, it’s worth noting that most easing cycles over the past three decades haven’t been too dramatic. Since 1990, the average sequence of cuts has taken around six months and featured just about nine 25-bps rate cuts before all was said and done (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Judging by Fed's History, Easing Might Be Over Fast

As rates were on the way up, we looked to past episodes of tightening for clues as to how long it might last and how high they might go. Now, with the Fed messaging the potential for a few cuts in 2024—and markets pricing in a few more, still—it's worth revisiting the central bank's history, focusing on the nine easing cycles observed since 1990. The longest and deepest was the one that started in mid 1990, when the Fed slashed rates to mitigate the Gulf War recession; unemployment reached 7.8% two years after cuts commenced, helping to explain why the Fed remained accommodative for so long. In most cases, however, easing was short and sweet, illustrated by the most recent example: two cuts over a span of two weeks, lowering rates by 150 bps when COVID hit in early 2020.

Magnitude of rate cuts vs. duration of easing, each Fed cut cycle, 1990 - 2020

(Source: Rayliant Research. US Federal Reserve.)

We also note that most past cases of rate cuts, especially the deepest ones, were in response to serious economic downturns: not exactly where we find ourselves going into this year. While some analysts have pointed to a so-called “cardboard box recession” (see Figure 3), economic growth has been strong enough in 2023 to make one wonder how urgently the Fed will seek to pivot away from restrictive conditions this year.

Figure 3: Are We in the Midst of a 'Cardboard Box Recession'?

Since the Fed began hiking in March of 2022, a range of economic signals have flashed warnings of an impending recession: from the Treasury yield curve—which inverted in July the same year and has remained so ever since—to The Conference Board Leading Economic Index, which tracks a range of macro variables and predicts a downturn ahead. One explanation for the US economy's apparent resilience in the face of such gloomy data is that America did experience a recession, it was just much narrower than the type economists typically identify with a slowdown. That squares with growth in shipments of cardboard boxes, which usually plunges near a recession and has been deeply negative since late 2021. It also jibes with a contraction in US manufacturing, which last December entered its fourteenth month, offset by strength in the services sector, allowing the broader economy to stay above water.

% YoY growth in shipments of corrugated products, billions of sq. ft., 3-month avg., Jan. 2000 – Sep. 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, Fibre Box Association, NBER recessions shaded.)

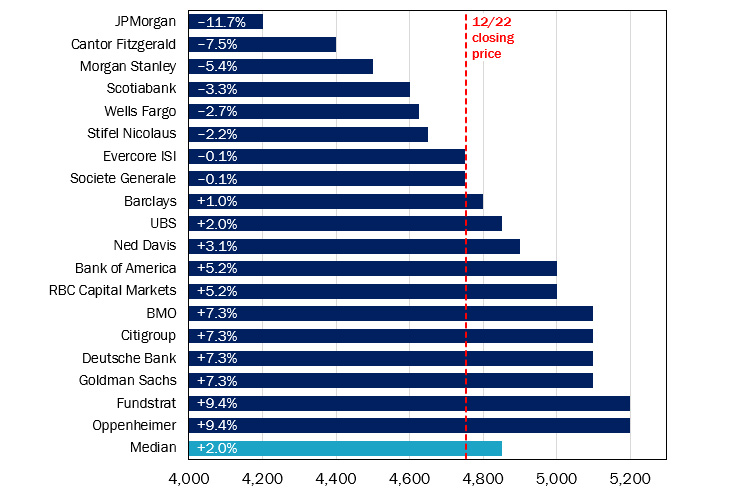

Another question always worth asking, particularly after a big rally in risk assets like we witnessed to close out 2023: How much of the good news is already priced? Like many market participants biding our time in the last few weeks of December, typically slower and lower-volume due to the holidays, we amused ourselves with the annual pastime of reviewing major market strategists’ 2024 outlooks. Interestingly, the median Wall Street projection in late-December put stocks on course for a mediocre year ahead, predicting just a 2% return for the S&P 500 over the next twelve months (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Wall Street Analysts See Modest Upside in 2024

Late in Q4, strategists at major investment firms posted their annual year-ahead outlooks for US stocks, with the median analyst predicting a 2% return on the S&P 500 in 2024. That's quite a comedown from last year's gains, though the median masks quite a bit of disagreement: JPMorgan expects stocks to close the year nearly -12% lower, while Oppenheimer's bullish call puts stocks ahead over 9% by December. Such year-end forecasts always generate major buzz, making it all the more important to recognize how prone they are to error. At the end of 2021, for example, Wall Street forecast stocks to rise by 4% in 2022. The market was actually down 19% for the year. And last year's 26% rally? Much better than the 6% gain analysts had penciled in at the end of 2022.

Forecast of 2024 S&P 500 return implied by various firms' year-end price targets

(Source: Rayliant Research, Bloomberg, as of Dec. 22, 2023.)

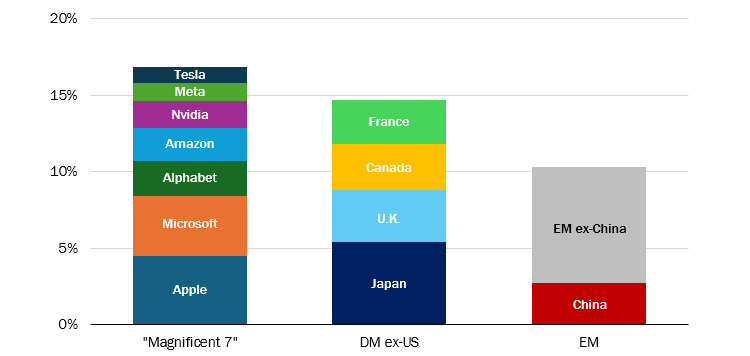

While one must take such forecasts with a grain of salt—they’re wrong about as often as they’re right—we tend to agree that there’s a good deal of optimism being baked into equity prices at this point, such that this year’s stock returns may turn out to disappoint. That’s especially true of US growth stocks exemplified by the so-called ‘Magnificent 7’, which ended last year at almost 17% weight in the typical global equity investor’s portfolio (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Many Equity Portfolios Closed 2023 a Bit More Concentrated

US stocks rallied to end 2023 on a high note after the Fed signaled rate cuts might be in the cards for 2024. But the top weights in the S&P 500—dubbed the "Magnificent 7"—had already posted huge gains earlier in the year, as enthusiasm around AI catapulted tech valuations, sparking debate as to whether the theme had achieved bubble status. Regardless of one's stance on that question, it's hard to argue last year's growth rally didn't lead to a fair amount of concentration in global portfolios: By year end, those seven US stocks' weight in MSCI's ACWI Index had reached almost 17%, significantly more than what the same portfolio allocated to the next four largest developed markets, combined, and more than six times the weight in all of China, the world's second-largest market.

Weight of various stocks in the MSCI All-Country World Index, as of Dec. 31, 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, MSCI. )

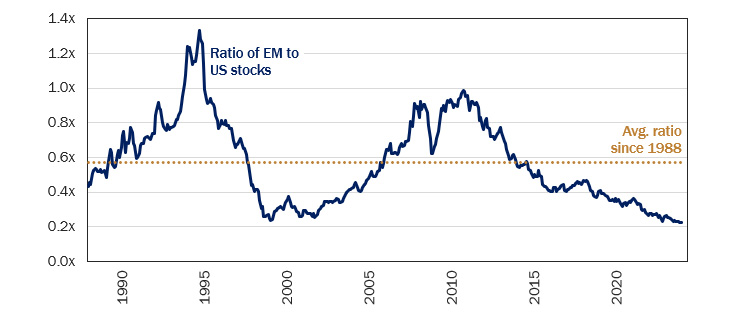

While there are a number of those mega-caps we like, at valuations like these, we see prudence in global diversification. That applies to developed markets outside the US, though the case seems even stronger in EM, where shares boast more attractive prices relative to those in the US than at any time in at least the last thirty-six years (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Emerging Markets Looking Cheap vs. U.S. Stocks

Another way of visualizing the impact of 2023's rally on US equities is to consider their valuation relative to other regions from an historical perspective. While emerging market shares traditionally trade at a discount to US stocks, never since MSCI data begin in late-1987 have EM stocks been priced as low against their US counterparts as in December 2023. Those looking for patterns will be drawn to the big decline in EM relative valuations in the late 1990s—a period marked by the run-up of America's "dot-com" bubble—and a more protracted slide since around 2010, after which US stocks entered a long rally under the influence of ultra-low interest rates. Those concerned with US tech stocks' valuation entering 2024 may favor a tilt toward more reasonably priced growth in EM.

Ratio of MSCI Emerging Markets to MSCI USA price indices, Dec. 1987 – Dec. 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, MSCI.)

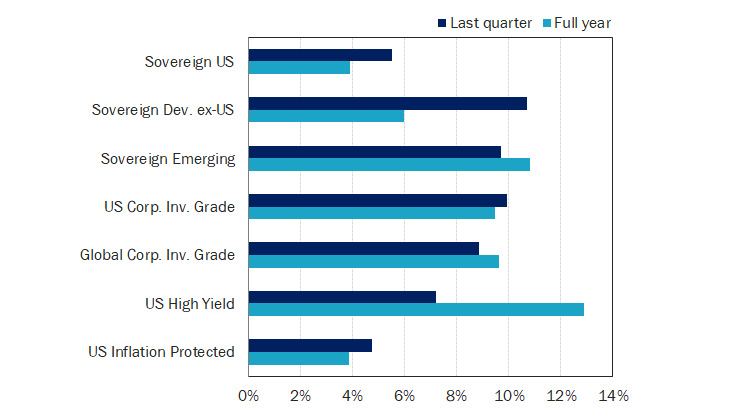

Fixed Income

With talk of Fed rate cuts taking center stage at the end of last year, it’s no surprise that fixed income posted stellar performance, with yields falling and bonds rallying across the board in the fourth quarter (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Fixed Income Market Performance (Returns as of 31 December 2023)

(Source: ICE US Treasuries Core, S&P Int. Sov. ex-US, JPMorgan EMBI Global Core, iBoxx USD Liquid Inv. Grade, Bloomberg Global Agg. Corp., iBoxx USD Liquid High Yield, Bloomberg US Gov. Inflation-Linked All Mat., all expressed in USD, via Bloomberg.)

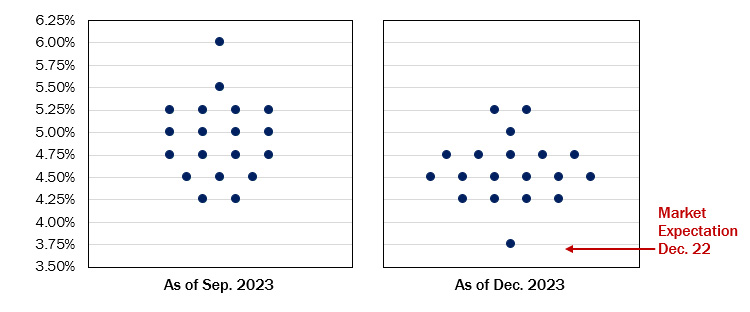

As we alluded to before, at the heart of this sudden shift in sentiment on the part of fixed income investors in Q4 was a rather surprising revision to the Fed’s quarterly dot plots at its December FOMC, showing a concerted move from ‘higher for longer’ thinking and contemplation of further hikes to tentatively penciling in three cuts by the end of 2024 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: December Dot Plot Shows Pivot in Fed's Thinking on Rates

Leading up to the FOMC's December 13th meeting—its last chance to adjust rates in 2023—traders were pricing a 99.8% chance the Fed would hold rates steady: not much in the way of suspense. Instead, investors focused their attention on the quarterly 'dot plot', a visualization of where each committee member stands on the future path of policy rates. That chart was truly a shocker, with the median row changing from September to imply three rate cuts this year, a major departure from Fed chair Powell's statement just before the pre-FOMC communication blackout period, that “it would be premature…to speculate on when policy might ease." As has been the case throughout the current policy cycle, traders quickly rejected the Fed's messaging, reacting by pricing in six cuts for 2024.

Projections for year-end 2024 Fed policy rate, last two 2023 dot plots

(Source: Rayliant Research, FOMC, Chicago Board Options Exchange.)

Looking beyond Treasuries, and consistent with the outperformance of risk assets more generally, investment grade bonds and high yield credit outperformed in Q4, as investors bet that easing financial conditions would coincide with a soft landing and, ultimately, less fallout from previous tightening than had been feared—although, with credit spreads at lower-than-average levels throughout most of this cycle, we don’t see this as a great entry point in riskier parts of the market.

Entering December, we also didn’t see such a dramatic pivot in the Fed’s messaging coming. Financial conditions are actually quite loose at the moment, considering we’ve just absorbed 525 bps of rate hikes, not least because the market has been prone over the last two years to severely discount the Fed’s resolve. Naturally, as if on cue, traders swiftly reacted to the dot plots’ implication of three rate cuts in 2024 by pricing in another three more, bringing the total cuts implied by Fed funds futures this year to six, with easing expected to commence as early as March. While we believe it’s reasonably likely the Fed is done hiking at this point, whether or not we even get three moves down in the Fed funds rate this year will ultimately depend on the path of inflation and the strength of the US economy.

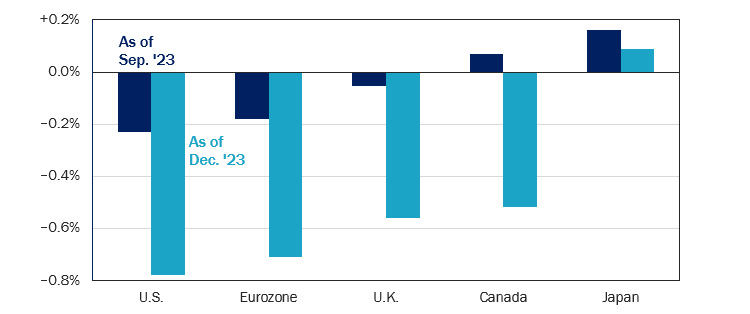

As such, despite a change in the Fed’s messaging, we believe their actual behavior will better match statements made by central bankers in Canada and Europe who, as of year-end, had not yet given in to investors’ plea for accommodation and still pledge a firm commitment to stomping out inflation—but whose markets have nevertheless also priced in aggressive easing in 2024 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Traders See Cuts Across Most Major Economies, Hikes in Japan

Just like the Fed, the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BoE), and the Bank of Canada (BoC) held the line in their final meetings of 2023, keeping rates at elevated levels through December in a bid to further quell inflation—which was actually falling faster in the Eurozone than in the US leading into year end. In contrast to the Fed's messaging pivot in the direction of easing, these other Western central banks refrained from signaling that the war against inflation might be over. The BoC's December statement even cited policymakers' willingness "to raise the policy rate further if needed." That didn't stop markets from pricing in hefty rate cuts for each of them in 2024, with the exception of Japan, where inflation is welcome and traders actually see modest tightening ahead.

Expected change in various central banks' policy rates in first half of 2024, as of Sep. and Dec. 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, Bloomberg, as of Sep 30, 2023 and Dec. 31, 2023.)

We suspect the easy gains against rising prices, mostly on the goods side, have been won, and that addressing the stickier service sector inflation will be a considerably bumpier road, perhaps upsetting the timeline suggested by those dot plots. As we’ve discussed at length elsewhere, we also see America’s fiscal position going into what promises to be an entertaining election year as putting upward pressure on yields and inflation beyond the Fed’s capability to easily fix, regardless of what it does with rates (see Figure 10). All of this leaves us considerably more bearish on longer-term bonds than the yield curve currently reflects.

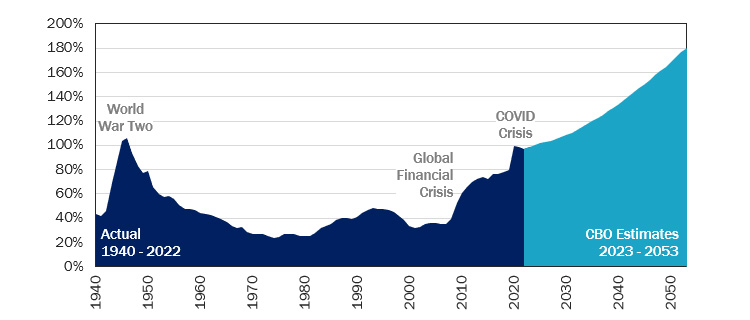

Figure 10: Ballooning National Debt Could Pressure Yields Higher

Although the prospect of rate cuts has driven a rally in Treasuries and pushed yields down from highs reached last October, Fed policy isn't the only determinant of yields. Another important input to valuations is the risk investors associate with loans to the US government. When markets get anxious about America's credit, investors demand a higher return on Treasuries and yields rise. That risk came into focus last summer, when Fitch downgraded US debt from AAA to AA+, citing America's precarious fiscal position, as Congress projects the national debt blowing through levels reached at the height of World War 2 in the next three decades. We do see high expected Treasury issuance and worries that US politicians won't rein in spending as continuing to exert upward pressure on yields.

U.S. national debt held by the public as a % of GDP at fiscal year end, 1940 - 2053

(Source: Rayliant Research, Congressional Budget Office, as of September 2023.)

Alternatives

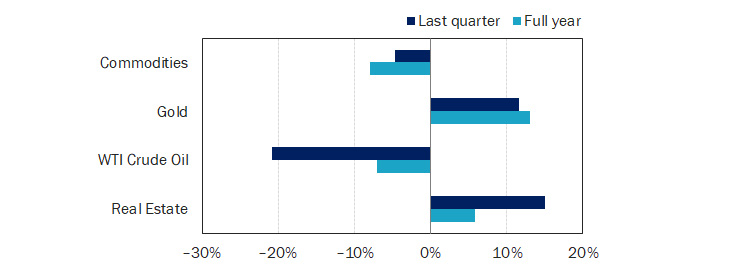

After two consecutive years of strong performance for commodities in 2021 and 2022—years in which the Bloomberg Commodity Index posted total returns of 27% and 16%, respectively—the asset class finished 2023 on a down note, falling -4.6% in Q4, and -7.9% for the full year (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Alternatives Performance (Returns as of 31 December 2023)

(Source: Bloomberg Commodity Index, Gold Spot, WTI Crude, iShares International Developed Real Estate ETF, all expressed in USD, via Bloomberg.)

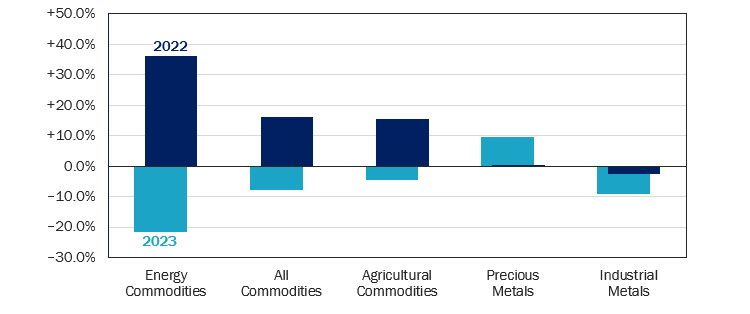

While rate cuts aren’t generally bad news for commodities (a weaking dollar could actually help among those settled in USD), most of last year was characterized by anxiety over global demand as manufacturing in many regions faced a contraction and weakness in China’s economy persisted. Despite tensions in the Middle East and OPEC+ supply cuts, energy prices slumped, with industrial metals and agricultural commodities also notching losses for the year (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: After a Strong 2022, Commodities Struggled in 2023

After strong outperformance of commodities in 2022—a year in which the logistical disruption due to China's zero-COVID policy set the stage for a massive shock to prices when Russia invaded Ukraine—the alternative asset class can perhaps be forgiven for delivering lackluster returns in 2023. Indeed, most sectors were down for the year, as markets processed Fed tightening and its implications for global growth, with China's dismal pandemic reopening further weighing on expectations for commodity demand. One bright spot was precious metals, propelled by gold whose price hit a record high of $2,135/oz. in early December as escalating tensions in the Middle East combined with bets on Fed rate cuts and a weak dollar to drive investors' interest in the non-yielding store of value.

Total return performance of commodities, overall and by sector, 2022 vs. 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, Bloomberg Commodity Index and Sector Indices, as of Dec. 31, 2023.)

One commodity that did benefit from expectations for Fed rate cuts was gold, which hit a record high price in December and boosted the precious metal sector to a gain of 9.6% for the year. Gold has historically performed better when rates are low, such that the opportunity cost of holding an asset generating no yield is less severe.

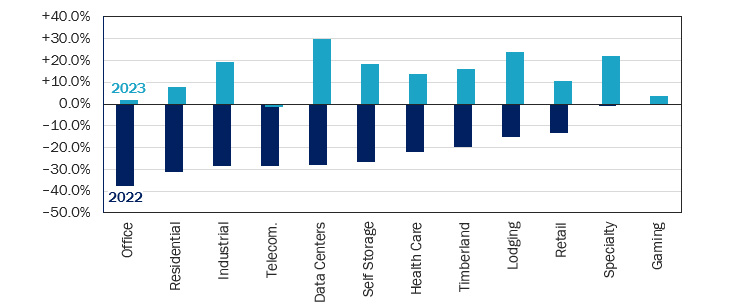

An alternative asset class with even greater interest rate sensitivity is the property market, for which a dovish pivot could not have come sooner. REITs are often used within an asset allocation to diversify a broader portfolio’s exposure, though rising rates over the last two years have been a major headwind. December’s shift in policy rate expectations led to a strong revaluation of real estate, with developed properties climbing over 15% in Q4, putting it firmly in the black for the year, up almost 6%. The bounce in real estate investments wasn’t uniform, with properties in the Industrial, Data Center, Lodging, and Specialty categories performing much better, for example, than those in the Office sector. That said, with the exception of Telecom—stifled by the effects of tight monetary policy on cell providers’ network expansion plans, finishing the year down modestly—every other property category registered gains for the year (see Figure 13). REITs may have more room to run, according to research on every Fed policy cycle since 1990, conducted by real estate industry association Nareit, which found that in the four quarters after a tightening cycle ends, public real estate funds have outperformed the S&P 500 by an average of 10.4%.

Figure 13: Last Year's Rebound in REITs Wasn't Evenly Distributed

Not surprisingly, given REITs fall at the intersection of the financial and property markets, the Fed's move in 2022 to aggressively raise rates led to losses for the asset class, with nearly every sector tracked by Nareit posting double-digit negative returns that year (the Specialty and Gaming segments were essentially flat). Near the end of last year, when the US central bank seemed to give in to investors' calls for a start to easing, real estate reversed course, sending most sectors of the market into the black for the full year in 2023. Among the worst performers in 2022, Office properties—still reeling from changes to the way Americans work post-pandemic—only managed a modest rebound, while Industrial powered back, and Data Centers ended the year with a whopping 30% return.

Total return performance of REITs by sector, 2022 vs. 2023

(Source: Rayliant Research, Nareit, as of Dec. 31, 2023.)

Economic Calendar

Key Economic Releases and Events for the United States – 2024 Q1

FOMC Rate Decision: 31st Jan., 20th Mar.

GDP Figures: 25th Jan., 28th Feb., 28th Mar.

PMI Figures: 1st Feb., 1st Mar.

CPI Figures: 13th Feb., 12th Mar.