AUGUST 30, 2021 | Dominic Ng

For more articles and related content, visit East West Bank’s digital business publication, Reach Further.

Dominic Ng, Chairman and CEO of East West Bank

With a new administration in place, East West Bank CEO and Chairman Dominic Ng says it’s time to reevaluate the effectiveness of the China tariffs.

Three years ago this summer, the Trump administration launched its first big wave of tariffs on Chinese goods, kickstarting the U.S.-China trade war. Despite the phase one deal signed last year, the U.S. maintains higher tariffs on two-thirds of all goods imported from China. President Biden, a critic of Trump’s tariffs on the campaign trail, has ordered a review of these policies. This marks an opportunity to reflect on what the trade war achieved, what it didn’t, and how to make the administration’s call for a worker-centered trade policy a reality.

First, a recap of the facts. Since 2018, the U.S. has imposed additional tariffs covering approximately $370 billion of U.S. imports from China. When these goods arrive at the U.S. border, U.S. companies pay taxes averaging 19% of the value of that product to the U.S. government. Studies have shown that nearly all the costs of the tariffs fall on American businesses, which pass these costs on to consumers through higher prices—costing each U.S. household nearly $1,300 in 2020, according to the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

These numbers may seem abstract, but when you speak to businesses hit by tariffs, you realize how these figures translate to fewer jobs, higher prices, and less consumer choice. Business owners I spoke to across a range of industries—shoes, home décor, seafood, furniture, and others—told me that tariffs forced them to raise prices and, in many cases, stop importing certain products altogether. On top of all that, the pandemic has led to shipping delays and soaring rates, amounting to a one-two punch against American companies.

The lucky ones cancelled plans to expand and hire new workers—but others have shut down entirely, in some cases moving their manufacturing operations (and jobs) to other countries where the tariffs don’t apply.

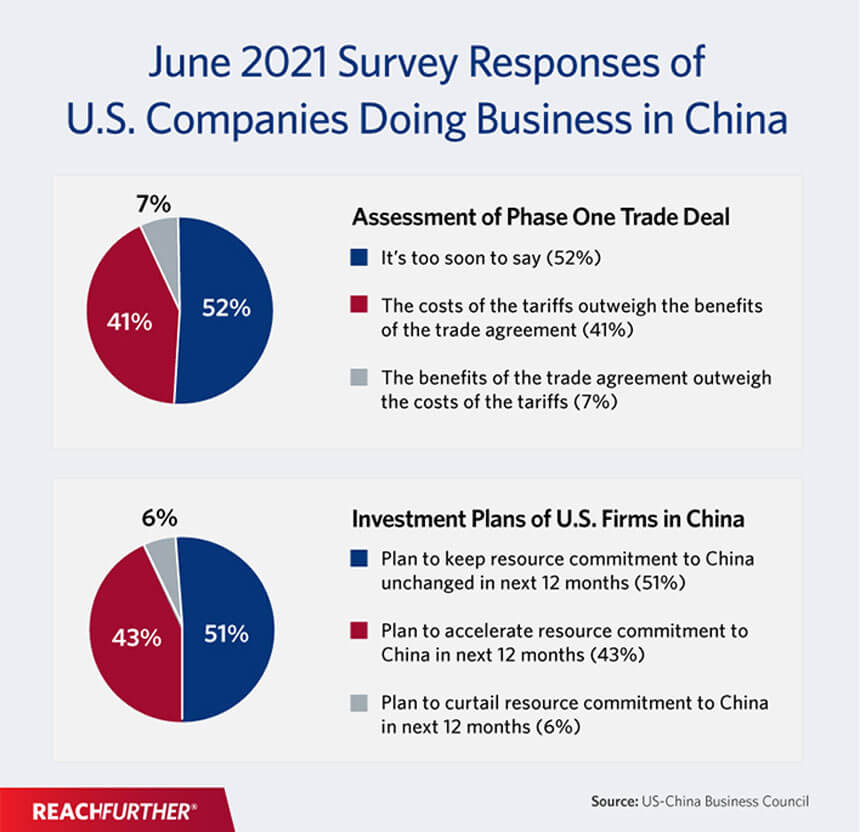

It’s not just U.S. importers, but exporters too. In a recent study, 82% of surveyed U.S. companies doing business in China reported that trade tensions have impacted their business in China, and 22% reported losing sales in China due to retaliatory tariffs. Yet for most of these companies, China remains a crucial market—only 6% of surveyed companies plan to scale back their resource commitments to their China operations over the next year, while 43% plan to invest more.

It would be one thing if the costs borne by American businesses and consumers led to a better deal for the United States. But the gains from the trade war are murky at best. In the first instance, the trade war failed to deliver on one of Trump’s main goals—to lower the U.S. trade deficit, a goal that never really made sense to begin with. The U.S. trade deficit is now the largest it has ever been, but for reasons that have less to do with China and more to do with strong U.S. consumer demand as the economy emerges from the depths of COVID-19.

US trade deficit and trade-related events, 2016-2021

Nor is there evidence that the trade war led to the reshoring of manufacturing jobs that Trump had promised. Official figures show that the number of registered U.S. companies in China has held steady, and a recent survey showed that only 2% of U.S. companies doing business in China moved segments of their supply chains to the U.S. in the past year.

The phase one deal did secure commitments from China to address intellectual property and forced technology transfer issues, but it has not delivered the results many had hoped for. Only 7% of surveyed businesses said that the benefits of the phase one deal have clearly outweighed the costs of the tariffs. At the same time, the phase one deal included provisions calling on China to buy record amounts of U.S. goods by fiat—a demand that sidelined U.S. allies and undermined the market-based norms of international trade that the U.S. should champion.

Survey responses of U.S. companies doing business in China

With the trade war lingering on, the business community and some in Congress are asking the administration to find a solution. It is unlikely that the administration will fully roll back its tariffs on China—to do so would invite accusations of being “soft” on China ahead of the midterm elections and 2024 presidential race.

Yet the administration can take steps to reduce the burden on companies in areas where the tariffs have been most detrimental. In the early days of the trade war, for instance, companies could apply for exclusions by citing severe economic harm or the inability to source the product from anywhere besides China.

But only a small fraction of those exclusion requests were granted, and most have since expired. For many small businesses, the exclusion process was too cumbersome and arcane to manage in the first place. The administration can renew exclusions for products where the impact on American workers is most severe. It can streamline the exclusion process and make it more transparent. Policymakers can even consider expanding the scope of goods eligible for exclusions, particularly for consumer goods and inputs that American consumers need but that have no strategic relevance whatsoever.

The Biden administration is right to call for a new worker-centered trade policy, putting the American worker first. As the administration considers its next steps toward the trading relationship with China, it should remember that average Americans are feeling the pain from tariffs more than anyone else.

This editorial first appeared on Forbes China.